Introduction

Tiny GPS units were applied to little / blue penguins during the 2015, 2016 and 2017 chick rearing seasons and the Trust collaborated with the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in a wider study to better understand the foraging patterns that were discovered.

A report was published in the NZ Journal of Zoology in April 2017, led by Tim Poupart and Dr Susan Waugh of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, and included data from three sites, Wellington, Motuara Island (Marlborough) and our West Coast study. Data has been collected for five years and, for three of those years, the West Coast Penguin Trust carried out the field work at Charleston and Cape Foulwind. Altogether the study includes tracks gathered on 68 individuals in three regions of central New Zealand between 2011 and 2016.

Foraging patterns varied between sites and between years. Tracks revealed that penguins can rely on distant foraging areas while incubating, with nesting birds from Motuara Island travelling up to 214 km to feed. Isotope analyses of blood samples showed that this distant food from deep waters (0–200 m deep) is likely to be squid dominated, which has a low nutrition value. During the chick rearing period, birds undertook a diet shift to a higher trophic level while foraging closer to their colony, and possibly near river plumes.

These findings highlight the need to consider much larger potential foraging ranges when assessing and managing threats to the penguins. The research team, including the Trust’s Kerry-Jayne Wilson and Reuben Lane, advise that conservation efforts need to take this variation into account to protect these penguins, which are currently in decline across New Zealand.

Phase 2

The Trust continued the project in 2019 with the support of the New Zealand Penguin Initiative. The NZPI was able to supply GPS trackers that also measured dive depths and although only two tracks were obtained, the information was very interesting and useful. Read more here.

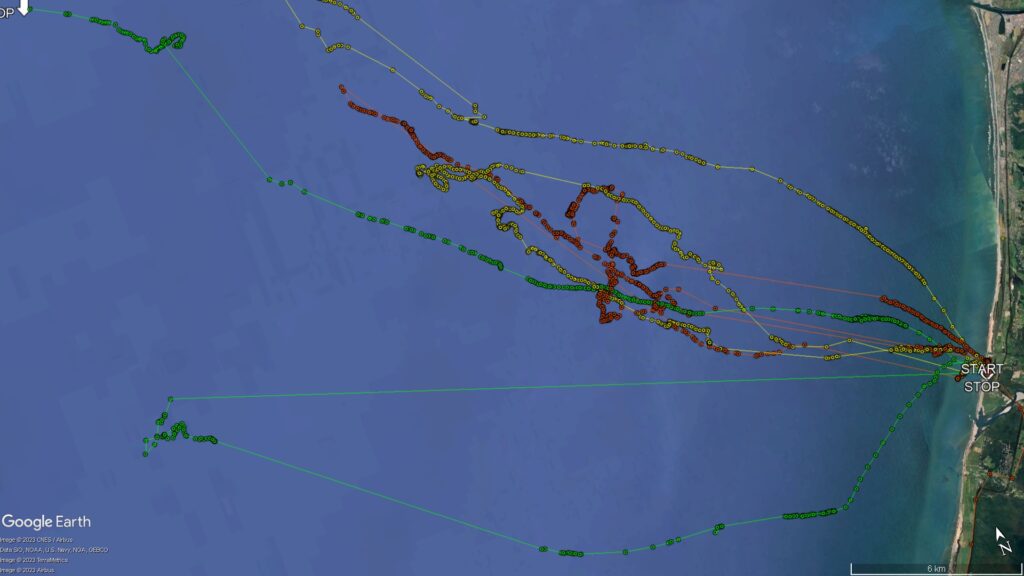

The study continued in 2020 with greater success and 11 tracks obtained illustrated below.

Phase 3

We had hoped to relaunch and extend our kororā foraging study during the 2022 season, with generous support from the Brian Mason Trust and the Environment & Heritage Lottery Fund. However, it quickly became apparent that the penguins were under stress, probably due to the marine heat wave*, and the call was made to cancel it for the season before it began to avoid further stressing the birds. Both grant funders kindly agreed to an extension so that the two year study could take place during the 2023 and 2024 seasons with the guidance of penguin scientist, Dr Thomas Mattern and new ranger Lucy Waller.

The site was moved to the Camerons beach colony for ease of access (closer to Ranger base in Hokitika, and penguin accessibility in nest boxes) and a pilot study undertaken there in September 2023.

Four birds were fitted with loggers from four different nest boxes. We had results from three of the loggers largely covering two trips per penguin. Recording of the second trips for two of the birds was not quite completed as the batteries failed. However, the six trip records gave us a first glance of the foraging journeys over three days made by those penguins. It showed they mostly stayed within 30km offshore to forage, which fits with our earlier studies from Charleston indicating that foraging remains approximately within the 110m bathymetric contour and an average range from home of 26kms.

Compared to a similar kororā tracking study that was conducted at the same time out of Port Taranaki, Camerons beach penguins travelled twice as far away from their nest sites to find food. This raises the question whether this is typical behaviour for the West Coast birds or a result of poor foraging conditions closer to the coast. Additional GPS tracking in 2024 at different stages of the breeding cycle will provide crucial insights.

More on the 2023 season study here.

We are very grateful to the Brian Mason Trust and the Lottery – Environment & Heritage Fund, for their support for this project this and next season.

We expect additional analysis of foraging areas in relation to other marine influences including currents, climate events and commercial fishing, to follow at some point, and for now, we’ll be focusing on ensuring consistency of process to collect data annually and contribute to an understanding of the foraging activity of blue penguins on the West Coast through key stages of the annual life cycle, namely incubation, chick rearing, and post chick guard stages.

We’d like to thank the JS Watson Trust (managed by Forest & Bird) for their support, Te Papa for their collaboration, and Dr Thomas Mattern for generous help, guidance and expertise.

Marine heatwaves

* The impact of climate change and marine heatwaves with likely increasingly adverse effects on little penguins is a concern. There are two theories as to the adverse effects of a marine heat wave on penguins. One theory is possibly due to intensified stratification resulting in reduced mixing of surface and deeper water. Thus increases in turbidity after rain events take longer to dissipate because sediments are trapped at the surface. As a consequence, the penguins have to travel further away from the coast to reach cleaner water where they can see adequately to catch prey. Stratification can also disrupt the usual vertical nutrient flow potentially resulting in higher productivity and algal blooms at the surface, which may also inhibit visibility. Alternatively, the intensified stratification also means that colder water and thus colder water prey fish are out of dive reach. DOC’s seabird specialist Graeme Taylor said in relation to hundreds of dead little penguins washing up on beaches in June 2022: “La Niña has combined with a marine heat wave to create a “double whammy” for the penguins, raising sea temperatures which in turn makes it more difficult for them to find the small fish they feed on, Taylor said. The fish may have moved south or descended to colder waters below the penguins’ diving range.” Read that story here.